Hypothermia

This will focus on accidental hypothermia; there

are numerous secondary causes that will not be the focus of this review.

Although typically associated with regions of the

world with severe winters, hypothermia is also seen in areas with warmer

climates, as well as during summer months and in hospitalized patients. Even with modern supportive care, mortality

for patients with moderate to severe accidental hypothermia approaches 40%.

Body Temperature reflects the balance between heat

production (cellular metabolism) and heat loss (evaporation, radiation,

conduction & convection). The normal

human core temperature is 98.6±0.9oF (37±0.5oC). The human body has limited physiological

capacity to respond to cold environmental conditions (basically, peripheral

vasoconstriction), thus our behavioral adaptations of clothing and

shelter. In response to a cold stress,

the hypothalamus attempts to stimulate heat production through shivering and

increased thyroid, catecholamine and adrenal activity. There is also sympathetic mediated

vasoconstriction of peripheral tissues.

Hypothermia is

defined as a core temperature below 95oF (35oC).

- Mild: 93.2 – 95oF (34-35oC)

- Moderate: 86 – 93.2oF (30-34oC)

- Severe: less than 86oF (less than 30oC)

Mild hypothermia is characterized by

tachypnea, tachycardia, initial hyperventilation, ataxia, dysarthria, impaired judgment,

shivering and “cold diuresis.” “Cold Diuresis” is renal-fluid wasting due to hypothermia-induced vasoconstriction

and diminished release of anti-diuretic hormone.

Moderate hypothermia is

characterized by a proportionate reduction in pulse rate and cardiac output,

hypoventilation, central nervous system depression, hyporeflexia, decrease

renal blood flow, and the loss of shivering.

Patients may begin to display paradoxical undressing. Atrial fibrillation, junctional bradycardia

and other cardiac arrhythmias may also occur.

Patients with severe hypothermia

develop pulmonary edema, oliguria, areflexia, hypotension, bradycardia, coma, ventricular

arrhythmias and asystole.

Risk Factors for hypothermia include: Age (infants

and the elderly), Environmental (exposure, drowning, and an alpine

environment), Poverty, Homeless, Drugs / Toxicology and Psychiatric disorders.

To measure the temperature in a hypothermic

patient requires a low-reading thermometer.

Most standard thermometers only read down to 93oF (34oC). If the patient is conscious, a rectal probe

thermometer is practical (although, to be truly accurate, needs to be inserted

15cm). If the patient is intubated, an esophageal

probe is preferred and is most accurate (inserted into the lower 1/3 of the esophagus).

What studies to obtain?

- Finger stick glucose! Do not miss the patient who is hypothermic secondary

to hypoglycemia. Remember, if the

patient does not have glucose, the body cannot generate heat to help rewarm

itself. Also, insulin release is

decreased in hypothermia, so hyperglycemia is common.

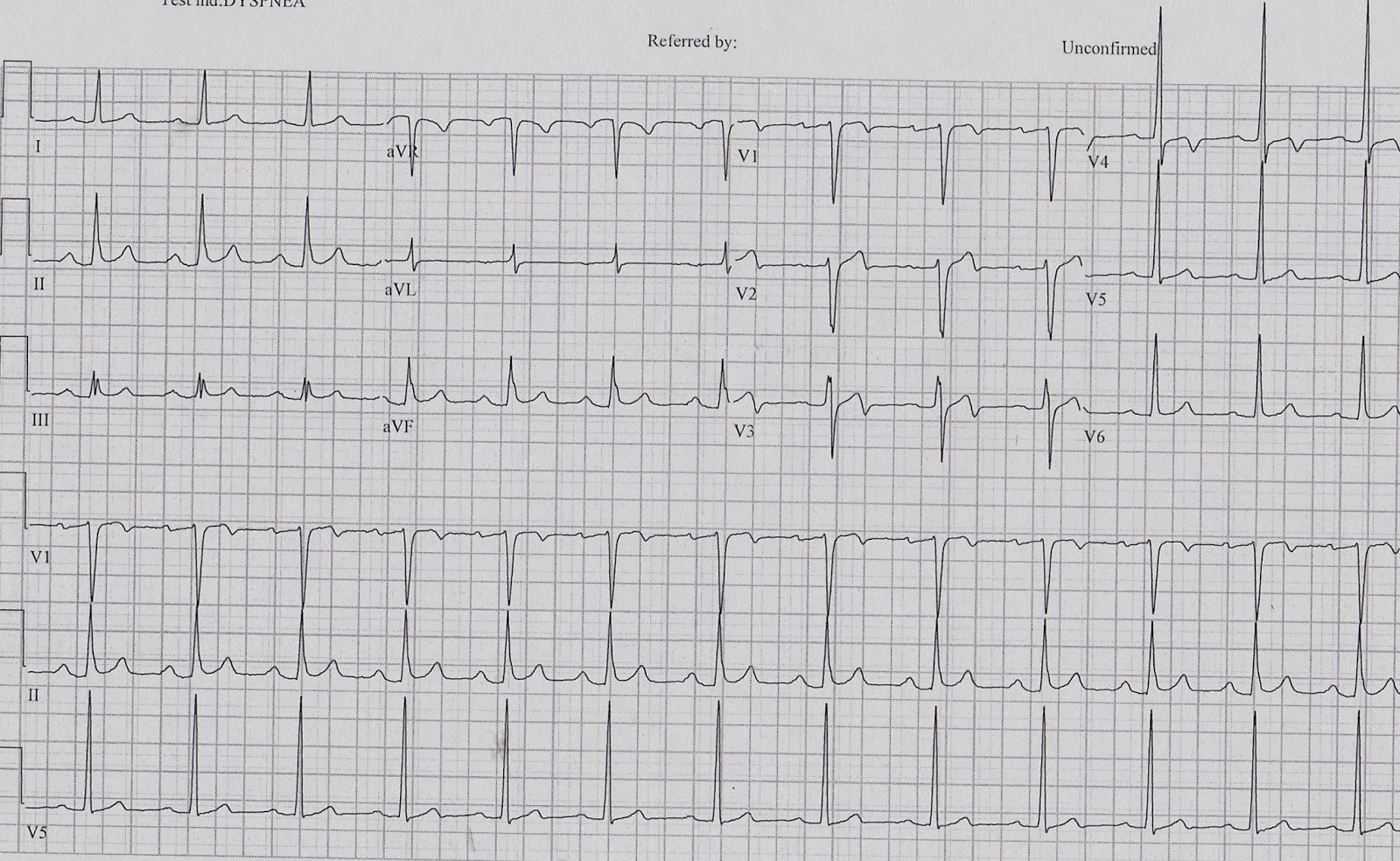

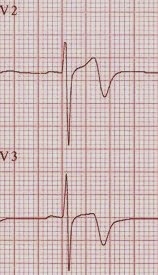

- ECG

- Hypothermia

causes characteristic ECG changes because of slowed impulse conduction through

potassium channels. This results in

prolongation of all the ECG intervals.

There also maybe elevation of the J point, producing the characteristic

Osborn J Wave (from the distortion of the earliest phase of membrane

repolarization).

- BMET

- Resuscitation

is futile if K >10

- Check

frequently during the resuscitation

- CBC

- There

is 2% drop in Hct for each 1oC drop in temp

- Thrombocytopenia

is common

- Lactate – elevated from shivering and poor

tissue perfusion

- PT/PTT – often coagulopathy is clinically evident

but laboratory studies appear normal as the test is run at 98.6F (37C)

- Fibrinogen

- Creatine phosphokinase

- Arterial blood gas – acidosis often present due

to severe respiratory depression and CO2 retention as well as lactic

acid production

- CXR – pneumonia (aspiration) is a common

complication

- Toxicology screen

- ETOH

Management

- ABCs

- There is an alteration in ACLS algorithm for

patients with severe hypothermia (less than 86oF (less than 30oC)). In patients with severe hypothermia, begin

CPR and attempt defibrillation once. Withhold

typical ACLS medications and any further defibrillation attempts until the patient’s

core temp is >86oF (>30oC). These patients will require active internal

rewarming (information below).

- Peripheral pulses may/will be difficult to

assess, check a central pulse for up to a minute and consider using doppler.

- Establish two large bore (14 or 16 gauge)

peripheral intravenous lines and start an infusion of warmed (100.4 – 107.6oF

(38 – 42oC)) isotonic crystalloid.

This will only really prevent further heat loss! If central venous access is needed, use the

femoral approach, if possible (to avoid the guide wire irritating the right

atria and causing an arrhythmia, which can occur with the internal jugular or subclavian

approach).

- Treatment of cardiac arrhythmia. Handle these patients with care! Movement has been reported to trigger

arrhythmias, including lethal ventricular fibrillation. Remember, bradycardia is expected and pacing

is not required unless the bradycardia persists despite rewarming to 90-95oF

(32-35oC).

- Typical

progression is sinus bradycardia to atrial fibrillation to ventricular

fibrillation to asystole.

- Rewarming Therapies

o Passive

External Rewarming (PER). This is the

treatment of choice for patients with mild hypothermia. Removal all wet and cold clothing and then

cover the patient in blankets or other types of insulation (aluminum foil). Set room temp to 82oF. PER

requires the patient to have a physiologic reserve sufficient to generate heat

by shivering and an increased metabolic rate.

If the patient’s temperature does not rise by 0.5-2oC/hr.,

reconsider the diagnosis (are they septic, hypoglycemic, hypovolemic, endocrine

source, etc.) and consider starting AER.

o Active

External Rewarming (AER). AER is

indicated for moderate to severe hypothermia and for a patient with mild

hypothermia who is unstable, lacks physiologic reserve or fails PER. AER is a combination of warmed blankets, heating

pads (watch for body surface burns from decreased sensation and reduced blood flow),

radiant heat, warm baths, or forced warm air, which are applied to the patients

skin.

§

Core Temperature After Drop is a risk during

AER. This occurs when the truck and

extremities are warmed simultaneously.

Cold, academic blood that has pooled in the extremities returns to the

core and can cause a drop in temperature and pH. This can trigger cardiac dysrhythmias.

§

Rewarming shock can occur when peripheral

vasodilation and venous pooling results in relative hypovolemia and

hypotension.

o Active

Internal Rewarming is indicated for severe hypothermia and those who fail to

respond to AER.

§

Airway rewarming is utilized by use humidified

air at 40-45oC.

§

Pleural irrigation can be accomplished by

placing two thoracotomy tubes (36 to 40 French), one placed anterior and one

posterior, and instilling warmed IVF into the anterior chest tube and allowed

to drain out the posterior chest tube.

If the patient is pulseless, use the left thoracic (bath the heart in

the warm fluid), if the patient has a pulse, use the right thoracic to avoid

triggering an arrhythmia by irritating the heart with tube insertion.

§

Bladder irrigation is another option

o Extreme

options (not readily available in many EDs): ECMO, hemodialysis, cardiopulmonary bypass

o Glucose,

if the patient is hypoglycemic

o Naloxone

o Thiamine,

as patients are often alcoholics (also, Wernicke’s)

o Hydrocortisone,

if the patient has a history of adrenal insufficiency

o Antibiotics,

for suspected sepsis

Remember, the patient is not dead until they are

“warm and dead.” But, how warm is warm? Target a temperature of 89.6oF (32oC)

in adults and a temperature of 95oF (35oC) in

children.

If the body is frozen and chest compressions are

impossible; or if the nose and mouth are blocked by ice; or if the patient’s

potassium is >10, then resuscitation can be withheld.

References:

Tintinalli Sixth Edition

Accidental hypothermia in Adults. Up-To-Date

Circulation. 2005;112:IV-136-IV-138.

Brown, et al. Accidental Hypothermia. N Engl J Med

2012;367:1930-8.